The Colonial Legacy: How inherited education systems shape Africa today

Volume III, Winter 25

Cornerstone EU

THE COLONIAL LEGACY: HOW INHERITED EDUCATION SYSTEMS SHAPE LEARNING IN AFRICA TODAY

Walk into most African classrooms today, and you'll find something striking: the curriculum, the language of instruction, even the exam formats often look like they were designed for children in London or Paris, not Lagos or Nairobi. That's because, in many ways, they were. More than six decades after independence in African countries, colonial-era education structures still shape how millions of African children learn. And the effects run deeper than most people realize.

Education Built for Empire, Not Empowerment

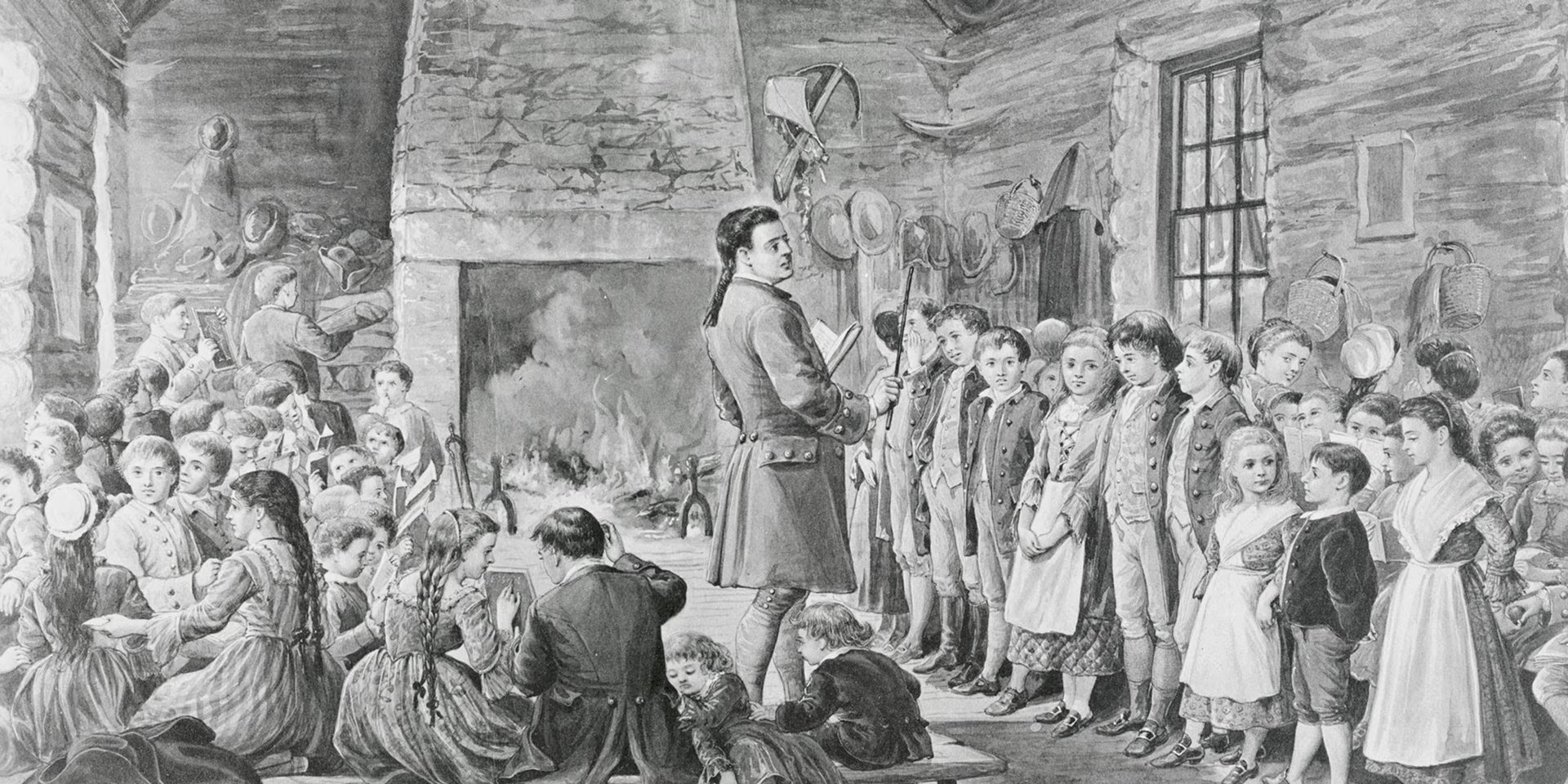

When European powers colonized Africa, they introduced formal Western education with a clear purpose: to create a small class of Africans who could work as clerks, interpreters, and low-level administrators. The goal wasn't to develop critical thinkers or innovators. It was to produce compliant workers who could help run the colonial machinery.

Frantz Fanon captured this reality in The Wretched of the Earth (1961), noting that colonial education was designed to "manufacture" obedient subjects rather than empower learners. Schools taught European languages, European history, and European values, while systematically erasing indigenous knowledge, languages, and ways of knowing.

Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong'o described the psychological damage in Decolonising the Mind (1986). African children learned to recite Shakespeare and memorize French kings, but their own stories, languages, and histories were labeled as uncivilized. The message was clear: to be educated meant to think, speak, and act European.

What Independence Didn't Change

When African nations gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s, many leaders wanted to overhaul education completely. Tanzania's Julius Nyerere tried introducing ujamaa education, a model focused on self-reliance, practical skills, and community values (Nyerere, 1968). While the system faced challenges in implementation and was eventually phased out, its emphasis on education for collective development and self-reliance continues to influence Tanzania’s educational philosophy and policy discussions today. But most countries kept the colonial systems largely intact. Building something new from scratch required money, expertise, and time that newly independent governments simply didn't have.

Fast forward to today, and the colonial fingerprints are still everywhere. Consider language: most African countries still use English, French, or Portuguese as the primary language of instruction, even though research consistently shows children learn best in their mother tongue (Bamgbose, 2011). Millions of students struggle not because the content is too difficult, but because they're being taught in a language they barely speak at home.

Then there's the curriculum itself. African students can tell you about the French Revolution or the British Industrial Revolution in detail, but many know almost nothing about their own liberation movements or pre-colonial achievements. This imbalance reinforces what scholar Ali Mazrui called "intellectual dependency"—the idea that real knowledge comes from the West, and African perspectives are somehow less legitimate (Mazrui, 1978).

Real Consequences in Everyday Life

These inherited systems create real problems. Exam-focused teaching prioritizes memorization over creativity and critical thinking, exactly the opposite of what Africa's young, growing workforce needs. Oketch’s (2007) observation remains relevant today, as vocational and technical training continues to be perceived as second-class education despite the ongoing global demand for skilled technicians, engineers, and tradespeople.

Perhaps most damaging is the disconnect students feel. When your education constantly tells you that your language is inferior, your history doesn't matter, and your culture is backwards, it's hard to develop confidence or imagine yourself as someone who can solve problems and create solutions.

Signs of Progress

It's not all bleak. Rwanda now uses Kinyarwanda in early grades before transitioning to English. South Africa has begun including indigenous knowledge systems in its curriculum, such as traditional healing practices, African mathematics, and environmental conservation methods used by indigenous communities for centuries. Across the continent, educators and activists are pushing for reforms that center African realities while still preparing students for a globalized world.

UNESCO's 2021 report Reimagining Our Futures Together emphasizes that good education must respect cultural diversity and local contexts, not just impose one-size-fits-all models from elsewhere.

The challenge is urgent. Recent data shows that while enrollment rates have improved, learning outcomes across much of Sub-Saharan Africa remain stagnant or are declining, with systemic issues hindering quality education delivery. African students also remain vastly underrepresented in global STEM opportunities, accounting for less than 3% of recipients in major international scholarship programs—evidence that inherited education systems still create barriers rather than pathways to excellence.

The Path Forward

The colonial legacy in African education isn't permanent. Change is already happening, driven by teachers, scholars, and policymakers who believe African children deserve education systems designed for them, not inherited from colonial administrators.

The real question isn't whether Africa should decolonize its education. It's whether we're ready to do the hard work of building systems that honor African languages, knowledge, and ways of learning while also equipping students with the skills to thrive globally. That's the challenge, and the opportunity facing African education today.

Fatimah A. Adebowale, Research Analyst at Cornerstone EU

Our Socials:

Contact us:

For Partnerships & Inquiries:

© 2025. All rights reserved.